- Home

- Sheila Forsey

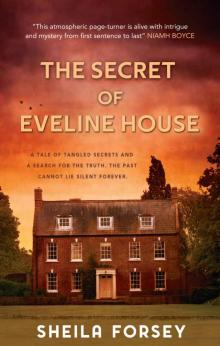

The Secret of Eveline House Page 6

The Secret of Eveline House Read online

Page 6

‘Alright, Mummy.’ Sylvia hugged Violet before leaving the room.

Violet sat down opposite Henry, her eyes showing new lines that had recently appeared.

‘We need to leave here, Henry – why will you not listen to me?’ she pleaded.

Henry shook his head. ‘For Christ’s sake, Violet, I am not being run out of my own country by some stupid old biddy with a stupid poisoned-pen letter. I am going to report it. Let that garda sort it out. I promise this will not end well for whoever wrote that poison. Be reasonable. There are biddies in every town. I am sure in time Sylvia will improve. Let’s get the doctor to look at her. Give her a bottle of something to build her up. It will all blow over.’

‘Blow over? How can all this just blow over?’

‘Why don’t we go out this evening to the hotel, just the two of us. It will do us good and Betsy will stay and mind Sylvia. You know she won’t let anything happen to her.’

Violet was weary. It was true – Betsy would watch her like a hawk. Maybe she should go. It might give her a chance to talk to Henry and convince him that leaving was the only answer. In truth, she had already decided.

‘Please, Violet, you have barely left the house yourself these past few days except to go to Blythe Wood. It will do you good, it will do us both good.’

Violet had continued to sleep in the guest room. Although she was barely sleeping. The fact that she had moved out of the main bedroom was not helping matters. It was driving a wedge between them.

‘Very well, let’s. I’m just going to lie down for a while, I feel so tired.’

She walked upstairs, back to the bedroom that she normally shared with him.

It was papered in an embossed gold, with plum-velvet drapes and a large four-poster bed. There were ornate bottles of French perfume and a gold jewellery box on the dressing table. A lady’s vanity unit lay open on a small table. A rose-gold hairbrush that Henry had bought for her sat beside some creams and potions she had bought in Harrods.

She pulled open the drawer and took out the photo of her parents. They looked so young in the photo, without the creases that life had inflicted on their faces.

She tried to imagine what her mother was doing. After all her chores of feeding the hens and the pig, she would have made some breakfast for the men who were busy with their own chores. Then after that perhaps made a wheaten loaf. Then she would set about getting the washing ready for the day. Her hands were hard and swollen from the work, her back aching from the scrubbing. Her mother perhaps no longer talked about her estranged daughter. Violet wondered if her name was ever even mentioned in her home.

An image of apple-picking came into her mind. They had a large orchard at the back, and it was brimming with the sweetest apples. Her mother would make apple jam, tarts and then wrap the apples not used in bits of old newspaper and store them in the pantry. She could remember how the sun felt on her face as she bit into one of those apples, her mother picking them and smiling at her. How she wished she could talk to her, ask for her help with Sylvia. Introduce her to her beautiful granddaughter. Sylvia would love the freedom on the farm and the kittens who nested in the shed. The birds who built their nests high up in the rafters, ignoring wars and woes, intent on building their homes for their babies. How Sylvia would fall in love with the colours of the heathers on the hillside and the brook where she could fish for minions! She could roam the countryside, picking blackberries just like she herself had done. How she would marvel at the lough as she imagined the three swans in the story of the Children of Lir!

But the morning she had sneaked out that door for England was the day she made her bed – she would have to lie in it now. The first year she had sent her mother a beautiful silk scarf. She could hear her say, ‘Sure, where would I wear such a grand scarf?’

But Violet knew that secretly she would love a fine thing like a silk scarf.

She lay back on the bed and thought about the evening ahead. She would have to convince Henry tonight. She slept for an hour and then got up and worked on her new play. But her mind would not settle.

She played cards with Sylvia for a little while and then caught up on some correspondence from the theatres. She wrote to some of her writer friends in London and then walked out to post the letters.

Towards evening she had a bath and washed her hair, spending time coiffuring it into a style behind her ears that she had seen in a magazine. She picked out a pale-blue silk dress with a full skirt and a wasp waist embellished with flowers. She was possibly a bit too dressed-up for Draheen, but she didn’t care. In her head she had already left. She took some time applying some gentle make-up and then her scarlet lipstick. Finally she put on her cream cashmere coat, red half-hat and cream gloves.

Henry whistled from the hall as she came down the stairs.

‘Well, you are a picture! Every eye in Draheen will be envious of me,’ he said, but Violet caught the look of tension that crossed his face when he saw her so dressed-up.

Clearly he would prefer her to dress in a lower key. The thought upset her. They had always dressed up when they went out in London.

But she was in Ireland now.

It was not too far to walk up to the hotel and, although cold, it was good to be out in the air. Henry bid hello to a couple of people. Violet could feel the stares. She held her head up high and walked on in step with Henry.

The hotel was busy as they walked into the foyer. There was a record-player and Bing Crosby was crooning. They sat and ordered a drink from the waitress, then said hello to the nearby table. John and Catherine Hunt from Blake House a few miles outside of the town were having a drink. The Hunts were Protestants who normally only mixed with their own. At another table were two brothers who lived in another big house called Blackburn Hall. They tended to eat in the hotel two to three times a week. Their father and mother were dead, and they were the last descendants of a long line of gentry. They wore tweeds and were known to smoke cigars and drink only sherry. They said hello to Henry and Violet.

After finishing their drinks, Henry and Violet walked into the main dining area of the hotel. This was known as the parlour. It had a small bar and a fire blazed in the hearth. There were two other tables busy and they nodded good evening to their occupants.

The owner of the hotel, Mrs O’Hara, was wearing a black dress with a starched white collar, her grey hair pinned high up on her head. She was cleaning some glasses behind a small bar.

‘Good evening, Mr Ward. Nice to see you out, Mrs Ward. Is it taking a break from your writing you are?’ Her tone sounded unpleasant and she surveyed Violet through narrowed red-rimmed eyes.

‘Only for the evening, Mrs O’Hara. I will be back to my writing first thing in the morning.’

Mrs O’Hara pursed her lips. She came out, took their coats and hung them on a coat stand. Then she showed them to a table.

‘Shall we have another drink first and then have a bite to eat?’ Henry suggested to Violet.

She nodded and they ordered a whiskey for Henry and a dry sherry for her.

She took off her gloves and put them into her bag, wondering when would be the best time to tackle Henry. Should she wait until he’d had a few more drinks? She sipped her sherry.

Henry threw back the whiskey and ordered another. He sat back, folding his arms.

‘I met with that carpenter today,’ he said. ‘A brilliant craftsman. He will do a fine job on the interior. We are just trying to source the wood. But it will look so polished when it’s complete.’

Violet could feel herself tense. ‘Henry, you are going ahead with the plans?’

‘Yes, of course I’m going ahead with the plans. Why wouldn’t I?’

‘After everything I have said? About the letter. How unsettled we are here. I thought we would discuss the matter further.’

‘The building is bought. The deal is signed. I cannot go back on my plans and commitments and quite frankly it’s the last thing I want to do. For Christ’s sake, give it a rest.’

<

br /> ‘I know you have invested heavily in this new building,’ she said. ‘But we can sell it, you can buy one in London.’

‘Violet, stop, I can’t listen to this talk from you anymore. We are not moving.’

Violet had a terrible sense of foreboding as he caught both her hands across the small table and lowered his voice. His grip was so tight it caught her off guard. He was staring intently into her eyes.

‘Violet, you are my world, you and Sylvia. I know it’s hard here, but it will get better, I know it will, I will make it my business to make things better. I hate all this distance. I know you are unhappy, but this is getting out of hand. We have each other and Sylvia, that is all that matters.’

Violet took her hands away. ‘How are you going to make things better? This place – this place will never change. I am constantly looking over my shoulder wondering who wrote that poison. Sylvia has not left the house. How is all that going to change? Tell me that!’

Henry spoke very quietly as if to a child. ‘I think you need to stop writing, just for a while, and perhaps let the people of the town know that you are taking a break from your career. It’s not unusual. Just until everything settles down. I know you love writing, but until Sylvia has settled?’

Violet could feel a panic inside her belly that almost made her throw up.

‘How can you even suggest it? I had put that kind of suggestion down to the likes of Miss Doheny. I didn’t expect you to join the army. This is what that evil letter was intended to do. To stop my writing.’

‘I am just suggesting that you take a break from writing. This new play can wait for a little while. Just a break. That’s all. Then, when things settle, we can see.’

Violet shook her head. ‘I can’t believe you’re saying this. You are blaming me for what is happening to Sylvia.’

‘Well, it is the writing that is upsetting everyone. They are just not ready for someone like you. I love you and want what’s best for you and everyone. I am just asking you to take a break from it. Just until we all settle here. You can redecorate the house if you like. Put your own stamp on it.’

Violet could feel her body stiffen. She tried to control her voice. ‘I don’t want to decorate the house.’

‘Well, maybe there is something else you could do. Maybe get involved in the community or something?’

Her stomach had turned into a gut-wrenching ache. It was getting very difficult to keep her voice low – she wanted to scream.

‘So, you want me to stop writing. Am I making a mistake on this? I need to be clear on what you want.’ Her voice was rising now.

‘Look, all I am saying is that perhaps if you took a break from your writing, the theatre, all those theatrical people, it might be easier to settle in.’

‘I cannot believe you are saying this.’

‘Violet, we need to be sensible – it can take time to fit in somewhere.’

‘But I don’t want to fit in! I want to leave!’ she hissed. ‘I want to go back to London. Henry, I am going back.’

Henry reached for his drink, throwing back the stiff whiskey.

‘My God, woman, I am trying to provide for my family, and I think I am doing a bloody good job of it. You are not giving Draheen or me a chance.’

‘Well, maybe it’s because most of the people living here think I am some sort of harlot.’

‘That’s some old biddy. I am trying to sort this out. Just give it a chance.’

‘No, Henry, that is not what you are asking me, and you know it. You are asking me to stop writing, stop my plays. Leave the theatrical world, the world that I adore. You knew who I was before you married me.’ She knew her voice was too loud, but it was impossible to whisper. She could feel people looking at her.

Henry had reached for a cigarette, lit it and breathed it in deeply. His face looked pale and strained.

‘You knew who I was too, and you knew I always planned to return to Ireland. It is my home and I am not being run out of it by anyone.’

His voice was colder than she had ever noticed it before.

Violet flinched. ‘Are you including me in that?’

‘I’m telling you, Violet – we are not moving. ‘

‘What are you saying? That I have no say in this? I must do as you tell me to?’ Violet stood up.

Everyone in the room was staring at them.

‘Violet, sit down!’ Henry hissed.

But Violet was picking up her gloves and bag.

‘No, Henry, I will not sit down.’

‘Violet, I order you to sit!’

‘I do not answer to orders.’

‘I need to make you understand, Violet.’

‘Maybe it’s you who needs to understand, Henry. I am going back to London and Sylvia is coming with me. I have left Ireland before, and I will leave Ireland again. With or without your blessing.’ Violet tried to keep her voice even, although inside she was trembling.

She turned to walk away.

Henry stood up and tried to catch her arm, but he missed her.

He called after her. ‘Don’t threaten me, Violet! I warn you!’

Violet’s heart was beating so hard she thought it would explode. Her legs were turning to jelly. She walked out of the room, leaving Henry standing alone, every eye in the room on him.

CHAPTER 10

It was as if her legs were carrying her of their own volition – Violet seemed to have no connection to them. She was numb, yet she was moving quickly. Away from the hotel up towards Church Road. The air smelled of woodsmoke, wood from the dead trees of Blythe Wood. She caught her breath with gasps from the biting cold. The night was still as if the frost hung in it. She wished she had worn flatter shoes. A strong urge to see the river that flowed through the town and was home to a family of swans overcame her. She began to walk towards it.

She needed the solace of the water to calm her mind. The river in Draheen was still pure and clear and in the late evening ducks would nestle in the reeds. She reached the river. The moon had risen and there was a glimmer of brightness that glinted over the water, casting shadows of light and dark.

Normally the water looked clear but this evening she imagined it looked muddy with secrets thrown in and hidden – a river full of conspiracies, prayers and memories of things not mentioned, things long forgotten or buried in the minds of some poor townspeople.

She almost tripped as she walked along, listening to the gurgle of the water against the reeds and the stones, her feet crunching on broken twigs and rotten leaves. When she had left the house earlier, she had never thought she would be walking alone this cold frosty night.

Well, they had certainly given the people of the town something to talk about. A mixture of anger and sadness washed over her. She looked around to see if Henry had followed her. But the road was silent except for the odd dog barking. A man on a bicycle bid her a good evening.

There was a pub in the distance, with an amber glow from the small window. How she wished she could go in and order a large drink and sit quietly to gather her thoughts. But she would certainly be the talk of the town if she did. It was not the thing for a woman to go alone into a pub in a town in Ireland. Suddenly the cold became almost unbearable, her coat no protection from the chill. She turned away from the river and walked back up the street, took the corner and went up Magpie Lane which would lead her to the road that Eveline House was on.

When she reached the house Betsy was at the door, leaving some milk out for Milky the big fat black cat who had decided Eveline had become her home. Milky liked to sit in the back garden during the day but at night roamed the streets of Draheen. Betsy looked up and seemed to be about to say something but obviously knew from Violet’s face all was not well. She rushed to Violet and put her arm around her.

‘Mrs Ward, you are shaking like a leaf and frozen with the cold. Where is Mr Ward? What’s happened? Is Mr Ward alright?

‘Yes, Betsy – let’s get inside. Mr Ward is fine. I just need to get some warm

clothes on.’

Once inside she rushed upstairs, took off her clothes and got into a comfortable nightdress, slippers and a dressing gown. She washed away the earlier make-up and the tears. She could feel the heat of the dressing gown seep into her. There was a knock on the door.

‘It’s only me, Mrs Ward. I brought you some tea.’

‘Thank you, Betsy, you are kind.’

Betsy brought a tray in and poured some tea into a china cup, adding milk and sugar.

‘Can I help with whatever is ailing you, Mrs Ward?’

‘If only you could, Betsy, but I’m afraid you can’t.’ She sipped the tea and could feel the hot liquid almost in her veins. ‘Is Sylvia settled?’

‘Yes, not a bother on her. She was drawing for a long time, and when she grew tired I put her to bed. She just had a few bites of dinner, but at least it was something. She is fast asleep.’

‘Thank you, Betsy.’

‘Did you have something to eat? You didn’t have time, did you? I can rustle something up for you.’

‘No, Betsy – but you get home for yourself. I can make some eggs later, but now I couldn’t eat anything.’

‘Very well, but there is some soup on the hob in case you’re hungry. I can stay, Mrs Ward, if I can help at all.’

‘No, Betsy. All is fine. I will talk to you tomorrow. But it is late for you to go home alone. Henry would have driven you home.’ If he was sober enough, she thought.

‘The evening air will do me good. I will be home in a few minutes.’

After Betsy left, Violet walked over to her daughter’s bedroom. Sylvia was indeed fast asleep. A feeling of pure love and determination came over Violet. She knew that there were going to be turbulent times ahead, but she was determined to leave for London with Sylvia beside her.

She loved Henry but tonight had driven a wedge through that. He knew how much her writing meant to her. He knew how difficult it was for her here. He also knew of her past and how she felt she could not live within such a society. It was as if her life was repeating. She had to leave her own family because they wanted her to conform and she knew, as much as she loved Henry and it broke her heart to leave, that it seemed to be happening again. What hurt her the most was the way he now looked at her, as if he was wishing she was different from what she was. Her father had looked at her like that up until the day she ran away. But it was harder when her mother looked at her wishing she was different. Now Henry. Now he had that same look. She knew that he would not change now. He had seemed more open in London. But being back in his beloved Ireland had made him less understanding of who she was.

The Secret of Eveline House

The Secret of Eveline House